The past couple of days have been quite museum-heavy, as Sunday spelled an opportunity for extra credit (visit the Museum of London and write about it), while Monday afternoon consisted of a class trip to the British National Museum (in short, utterly BRILLIANT!).

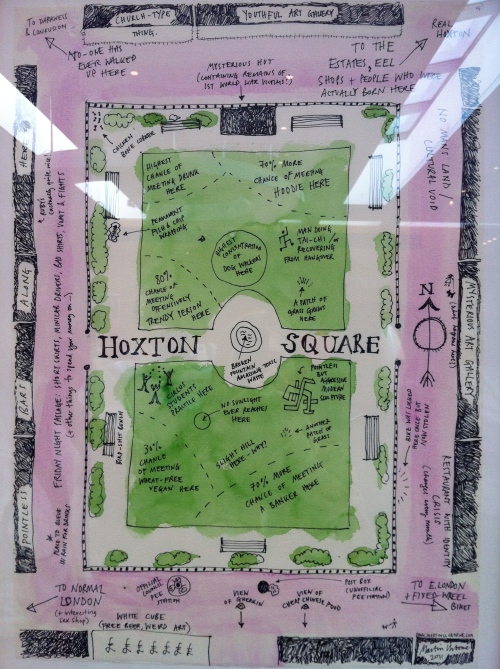

22 May, Kristin and I slept in slightly, had a quick breakfast of tea, pan-crisped prosciutto, and oatmeal with golden syrup, and took the tube over to the Museum of London with Miss Clara and a couple of guys on our trip. The objective of this museum visit was to extensively go through three exhibits (preferably pertaining to the time periods covered in our classes), and then write about the exhibits for a whopping 10 extra credit points (on top of the 6 point quiz that we… let’s just say most likely did not quite master too successfully). It was incredibly windy when we got off the tube, however it made a fantastic show of my long trench coat, as it billowed to and fro in the breeze. The museum itself was rather neat, as it quite literally (shocker, I know) covered the history of just London from its earliest, prehistoric roots, up until the present day (there were Blackberry phones on display, I kid thee not). Before we entered the exhibit areas, we were greeted by a wall of hand-painted and/or sketched maps of London. This one in particular caught our eyes… do take the time to read every inch of it, as it is quite humorous, and pardon the glare, if you’d please:

The first exhibit we visited was that concerning London before it was London or even Roman Londinium; this was all about prehistoric London, fraught with all sorts of beasties (like the wooly rhinoceros!), homo (the genus, not sexual orientation, people…) and neanderthal ancestors, the earliest tools, foraging methods, and the like of those ancestors’ doings. Frankly, it reminded me much of my honours history of food class the semester before last, but a smidgeon lighter on the food elements. As is to be expected, prehistoric London experienced waves of colder and warmer climatic periods, with human ancestors adapting accordingly, relying mainly on hunting and gathering, with the increased use of tools. These tools were at first made of flint, and hand axes were discovered in what is modern Piccadilly, dating back to 300,000 B.C. Tools were also made of bone, antler, and quartzite. About 8500 years ago, the rising seas finally cut the British Isles off from the rest of Europe, initiating its advantageous isolation (with regard to disease, cultural development and the maintenance of kingdoms much later). A really fascinating thing I learned was that London used to be covered in ancient forests, now having long since been drowned by the River Thames. A few photographs…

Flint hand axes, c. 300,000 B.C.

Flint hand axes, c. 300,000 B.C.

Flint hand axes and flakes, c. 300,000 B.C.

Flint hand axes and flakes, c. 300,000 B.C.

Wooly rhinoceros skull, flint leaf point, flint knives, spear tips, and long blade tools.

Wooly rhinoceros skull, flint leaf point, flint knives, spear tips, and long blade tools.

The second exhibit was largely archeological in scope, namely because it followed the rather tedious, albeit fascinating process of finding and carefully removing fantastic artifacts from their burial places. Here, we began to delve somewhat into the early Britons. There were a few more tools, and weaponry befitting grand, Anglo-Saxon battles depicted in Old English epics of yore! Moving along, we found Roman Britannia, specifically the city of Londinium, built roughly around A.D. 50. Britannia was first invaded by Julius Caesar, himself, who claimed Londinium as his own, forcing the city to pay duties to the Empire every year (which of course they did not pay). From then on, Londinium expanded quite rapidly, as it was indeed now a Roman city. As quite the hub for European trade (heavy on the imports), Londinium also was a bastion for Roman culture, flourishing wealth, and forging ahead by means of modernity and progress. Roman London was known for its bath houses, the rather large wall build around its entirety (by A.D. 220), its coins, architecture, and waterways. With the fall of the Roman Empire came the disintegration of Roman control over London, opening the city to increasingly invading Saxons that would define “Englishness” or “Britishness” to come. Dark ages they were, indeed. Now for the photographic evidence!

Tombstone of a Roman centurion, 3rd century.

Tombstone of a Roman centurion, 3rd century.

Horse skeleton and harness, 2nd century.

Horse skeleton and harness, 2nd century.

Equestrian tools, 2nd century.

Equestrian tools, 2nd century.

Roman medical instruments, 3rd – 4th century?

Roman medical instruments, 3rd – 4th century?

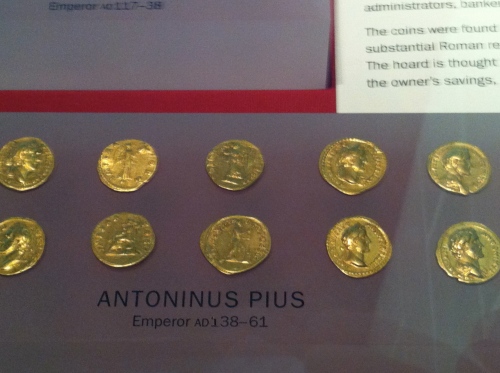

Gold coins, specifically those of Emperor Antoninus Pius, A.D. 138-61.

Gold coins, specifically those of Emperor Antoninus Pius, A.D. 138-61.

At about A.D. 550, Britannia fell under Saxon control after London essentially became a bit of a ghost town (that is, once the Romans decided to fail miserably in the art of ruling an empire). The Germanic Saxons thus mingled with the English/Britons/Angles, henceforth the Anglo-Saxon “race” was fashioned, accordingly. Britannia was forging into the infamous Medieval Age, fraught with courtly love, rampant religiosity and a wee smattering of holy crusades, an obsession with royals (we still have this), Arthurian legend, and knights in glistening armor and chain mail, clacking coconut shells, and an enchanter, whom some call… Tim! Okay, okay, not the last two. Getting back to reported history, this period was characterized by, among other things, many small kingdoms, farming, and marked the founding of ‘Lundenwic’ by the Anglo-Saxons in the 600’s. Lundenwic was controlled by the East Saxons, who inhabited what was formerly Roman Londinium. The West Saxons, led by King Alfred (or Ethelred- what a name!), gathered an army and took over Lundenwic, re-christening it Lundenburg, and built up the city once more. Curiously enough, Alfred was the only British monarch to ever be called “Great.” Others held the burden of such epithets as “the Unready” (a failed translation of “ill-counciled,” alas still unfortunate), the “Black Prince” (because he fancied wearing the colour), and “the Confessor” (as this particular king went to confession every day). 1066 saw the Britons fall into the hands of the Normans (les Francais!). The Normans also contributed heavily by way of architecture (the castle), government (the feudal system), food (I could go into a whole diatribe about the Norman influence on English cuisine, but I shall forgo that to expedite this a bit), and language (modern, as opposed to Old English, with all of its glorious, dualistic, and nonsensical grammatical structure and word usage).

It was also during this time (well, later, as it was in the 1300’s) that London, Lundenwic, Londinium, or Lundenburg experienced that hideous little disease known as the Black Death. It seems that Mum has an even more legitimate reason to completely loathe and deplore vermin (I assume most people do not take too well to plague carriers, am I right?). Anyway, the Middle Ages also spelled a time for building grand churches, and expanding/progressing industry (mainly cottage, I believe), and government (Parliament finally began meeting somewhat regularly in Westminster c. A.D. 1000). Religion held a very grand, strong role in society and in government, especially if you were the Archbishop of Canterbury, as was (later Saint) Thomas Becket. Becket has a fun story- basically, he made a big fuss when he disapproved of the king overstepping his lawful boundaries, the king did not enjoy Becket’s condemnations, thus Becket was murdered by four knights. With four blows to the head, the first of which shaved off the top of his skull, revealing the brain, with the following finishing off the poor guy, leaving his ravaged skull and brain matter open for an all-out buffet. A buffet, that is, for relic-making. Anyone for a handkerchief soaked in Becket’s blood? No? How about rubbing a bit of it in your eyes? Yes, people did do these things with all of his blood and brain loveliness. Not so civil, methinks.

Chain mail shirt, swords, jousting badges, harness decorations, and a buckler (small shield), A.D. 1300’s.

Chain mail shirt, swords, jousting badges, harness decorations, and a buckler (small shield), A.D. 1300’s.

Tailor and textile accessories, tools, dyes, weights, and custom seals, A.D. 1300’s – 1400’s.

Tailor and textile accessories, tools, dyes, weights, and custom seals, A.D. 1300’s – 1400’s.

“Cookery” equipment: fish hooks, spit, dripping pan, skimmer, beer mugs, pots, etc.

“Cookery” equipment: fish hooks, spit, dripping pan, skimmer, beer mugs, pots, etc.

Chalices, patens, vessels for wine, oil, and water, vases, figurines, and prayer beads, A.D. 1400’s – 1500’s.

Chalices, patens, vessels for wine, oil, and water, vases, figurines, and prayer beads, A.D. 1400’s – 1500’s.

Bibles and books, examples of Blackletter and Roman printing type.

Bibles and books, examples of Blackletter and Roman printing type.

Pair of salts (A.D. 1550 and 1552), The Leigh Cup (A.D. 1513), and The Wagon and Tunn (A.D. 1554).

Pair of salts (A.D. 1550 and 1552), The Leigh Cup (A.D. 1513), and The Wagon and Tunn (A.D. 1554).

Moving swiftly (or not so swiftly) along, we toured the exhibit entitled “War, Plague, and Fire: 1550’s-1660’s,” to which Kristin said, “War, Plague, and Fire? Good, because if there was just War and Plague, I’d say let’s leave” (ahh, the sarcasm!). As to be expected (I find the English are incredibly straightforward in names and titles- perhaps to make up for their strange grammar?), the war in this exhibit was mainly the one and only English Civil War and a brief touching on Elizabeth I’s war with Espana. As for plague, it returned, and the great (actually quite terrible) London Fire rounds out the exhibit title beautifully. Somewhat randomly, there was a model of the Rose Theatre, which housed playwrights such as Shakespeare and Marlowe before the Globe was erected. Theatre was an increasingly important fixture in London culture, much to the chagrin of those fun-sucking Puritans. Unlike the Globe, the Rose did not burn down, thus its inclusion in this specific exhibit is slightly odd (outside the prescribed time periods, that is). The remainder of this exhibit housed models of 17th-century home interiors and more bits pertaining to the 17th-century plague resurgence, its associated medical tools (and others), and descriptions of medical practices with the disease, and the like, concluding with a film on the London Fire. Fun fact: the first modern taxi was called a sedan chair, which is basically this lovely wooden box in which wealthy Londoners were carried by two footmen (as to not dirty their fancy shoes with the filth that was- and probably still is- the London cobblestone road).

Tip: Take caution when viewing 1550’s-era portraits, as they may be haunted. One of the guys, Dan, was taking a picture of some portrait with his digital camera, and blink detection popped on. Allllrighty, then. “I was just taking a picture of the portrait,” he said, “and blink detection came on. Moooving away, now.” Indeed, sir. Indeed.

Medical equipment for the plague.

Medical equipment for the plague.

The final two exhibits through which we dashed were those on Victorian Britain and Modern London. Victorian Britain held all sorts of gorgeous china, gold and silver items of any persuasion, clothing, shoes, watches, chairs, and anything entirely extravagant, beautiful, and expressive of grandeur and wealth (cheers for the British Empire!). Essentially, almost all of the items and goods produced during this time (and housed in this exhibit) were showing off the far-reaching extent of the Empire, its power, wealth, imperviousness to frankly laughable outside threats, etc. For instance, there was this one incredibly lovely golden yellow dress made of Chinese silk I really wanted to snag from the display case- it even looked like it was my size! To return, the imported, foreign, and expensive Chinese silk, crafted into an English, Victorian silhouette acted as just one instance of Empirical expression. Modern London was pretty cool, as it exhibited lots of wonderful clothing from the 1960’s to the 2000’s, a stunning stagecoach previously used by the Lord Mayor of London, children’s toys, telephone systems, typewriters, and as mentioned very much above, the Blackberry. Crackberry? Blackberry, which was not too far from the stage coach, early 20th-century military garb, and swords. With that, I shall exit the museum description and segue into the remainder of our day. We parted ways with the boys, went off into a different direction, eventually whipped into a Pret for a few “take away” sandwiches (’tis take away, not take out or ‘to go,’ in Britain). The remainder of our evening was spent relaxing, nibbling on sandwiches, drinking tea, and doing a wee bit of homework. Another blog is on the way, and with luck, quite hastily (albeit lovingly put together).

Chinese silk-damask dress, c. 1760.

Chinese silk-damask dress, c. 1760.

Uniform of St. George and grenadier’s cap, c. 1742 and c. 1750, respectively.

Uniform of St. George and grenadier’s cap, c. 1742 and c. 1750, respectively.

Watches produced in London, c. 1750’s.

Watches produced in London, c. 1750’s.

I really enjoyed this museum when I went through it. A very good representation of London indeed.

You just had to make a Monty Python reference… too funny (and shameless)!I think everyone (except people in the USA) call it take away… it sounds so much more civilized, don’t you agree?

Great seeing you on skype yesterday.

Alex’s graduation went well. She was delivered home at 5:15 am – and she was exhausted!

Love you!